Q-talk 24 - Q-NEWS - LETTERS - Q-TIPS

- Details

- Category: Q-Talk Articles

- Published: Wednesday, 31 October 1990 06:11

- Written by Jim Masal

- Hits: 3130

Dear Jim, Oct. 15, 1990

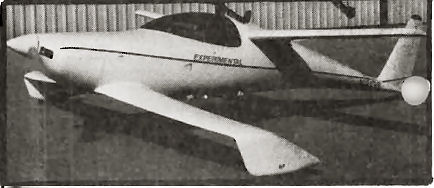

Well my aircraft has finally flown! The stats are: Empty weight 685 lbs. The plane is a Q-200 with a Warnke prop 70" pitch x 60" (max speed 173 MPH), Belly Board, Reflexor, Extra 9 gal. of gas behind pax (33.5 total), dual rudders pedals, wide tail wheel with 3/4" fiberglass tail spring, Radio, Loran, Transponder, 4 NASA air ducts, 50% more rudder, individual hand brakes, elevator roll trim, wide trim range reflexor.

My first flight came after I had taxied a while. The plane was real SQUIRRELY on the ground in the range of 40-60 MPH with power off. I finally got convinced that I should just take the plane off once to see how the plane performs in the air since the controls felt fine at the higher airspeeds. The aileron steering is quite effective and takes a little getting used to. I held the aircraft on the ground until about 80 MPH. When I pulled back on the stick - I was airborne. I was able to trim out the pitch force with REFLEXOR (ailerons up about 2" - yes, 2"). The cylinder head temp was rapidly rising as I was climbing and I was also on downwind so I decided to land. On final trying to land, a plane took off opposite direction so I went around. The CHT and oil temp really shot up as I applied power so I did a 180-degree turn at the end of the runway and set up for final. 90 MPH felt real comfortable so I held that until over the runway. With the power back, the aircraft just floated. The plane touched down first on the main gear, then the tail wheel, then back to the main in a kind of hobbyhorse fashion. Each oscillation seemed to get larger until it just settled down to rolling (not enough lift?). The plane was still traveling pretty fast and not appearing to slow down so I cut the engine and finally coasted to a halt. Whew!!! Arrived Alive!

Since that first flight I have made many changes and have 34 hours. I will list these by major category.

Engine Air Inlets - I had air inlets on the top cowling just above the split line because it was a straight shot by square a fiberglass duct to the pressure area above the engine (simplicity). The air probably could not make the sharp bend from the cowling to intake opening and the air just bypassed the inlet. I changed inlet opening to below the split line, put in large radius turns and built a serpentine converging-diverging duct that feeds the pressure area above the engine (CHT now runs 180-220 F - probably too low).

Oil Temp - It has consistently ran hot (200-225 F) so I added extra baffles to put all the air coming off the cylinders towards the center and across the oil tank. It still runs hot. I have two options left. I can use an oil cooler or route some outside air over the tank.

Sparrow Strainers - I originally did not put sparrow strainers on the aircraft. The trim spring was not able to hold the elevators in proper position and the air loads pushed the elevators up. To balance the lift the ailerons had to be reflexed up so much (the 2") to make the handling manageable in terms of stick forces. I put on the "factory" XEROXED side plates and a 12" airfoil about 24" outboard from the side (outboard of the prop slipstream). This helped a lot but the plane still pitches down at high speed (180 MPH+) and can't be trimmed out. When the airplane is slowed down the trim spring tension pulls the elevators down which makes the nose pitch up. I am going to change the location of the sparrow strainers from the in trail position to a position above the elevator and allow some means of changing the angle of attack until I have the right "feel".

Brakes - I had a single master cylinder feeding both brakes but the plane was hard to control with just the tail wheel. I had made provisions for dual brakes so I put them both in. I like dual brakes better. The master cylinders are mounted in front of the instrument panel and tee handles come through the panel just above the throttle. I can apply equal pressure or put more force on one brake handle or the other and I have a lot better control.

Roll - This plane wants to roll left and the differential elevator that I have put in (approx. 1") is just barely enough. I don't know whether this is due to misrigging, prop torque, or because I am on the left side.

Yaw Stability - This plane will stay yawed in either direction once put there (about 10 degrees either side of center). This is at medium (120-150 MPH) speeds.

Center of Gravity - My plane is on the forward edge of the envelope so the rear tank is used for live ballast. I also put 3 lbs at the tail wheel and probably could use more.

Landing - I generally use 90 MPH for final and have a shallow glide angle for the last couple hundred feet just prior to reaching the runway. I just hold the plane off until the tail wheel touches at about 75-80 MPH. This brings the angle of attack down and the mains touch. I can usually rollout straight with rudder and aileron steering until the plane gets to a speed range of 20-40 MPH. Then I have to use differential braking to slow to a taxi speed. If the power is not all the way off the plane it is hard to slow down! If I land on the main wheels the lowering of the tail wheel increases the angle of attack and the front wing produces more lift plus the springy front wing raises the nose and sets up the hobbyhorse rocking as the weight is transferred from front wheel to tail wheel. It finally stops but may get so rough as to break the tail spring (I did).

Performance - The performance in the air is great. On takeoff at 90 MPH I see 1500 fpm (sea level) but the nose is so high I can't see where I am going. I usually climb out at 120 MPH just to see. My minimum pitch buck speed is 60 MPH but the nose is so high I could not possibly land. At high G loading the pitch buck is at higher speeds.

Aileron Reflexor - Works great. I have a push pull cable to a turnbuckle in the cockpit. The other end is connected to a phenolic bearing block that rides up and down in an aluminum cage. I had a lever on the left side near the throttle so could reflex the ailerons up about 45 degrees to quickly kill lift on landing. It did not seem to work so I simplified the arrangement to just the turnbuckle. This turnbuckle works fine. I usually trim the aircraft so the elevators are flush to above flush in cruise. I can just see a little over the nose in this condition and the plane goes the fastest. The reflexor as it is moved up also causes the elevator to move up to maintain the altitude I am at. I try to have the elevators in trail at 90 MPH to give me enough pitch authority for landing. If I don't reflex the main wing up enough the elevator is full down (stick all the way back) at landing speed and I had better planned my flair right or I will slam on the runway. The only option then is to go around.

Larry Koutz - Flying High!

Dear Jim:

After talking to several Q-200 and Tri-Q-200 builders I learned that one of the biggest headaches to maintaining their engines was the difficulty they'd experienced while cleaning the oil screen on the rear of the engine during routine oil change operations. Some said they would have to pull their engines while others came up with some "Rube Goldberg" tool to accomplish this blind operation.

The best solution was from those that provided access to the screen thru an opening in the rear of the magneto box. I'd made several drawings of access holes that started with servicing only the oil screen to complete exposure of the accessory section of the engine. Finally I came up with a compromise in which all engine controls and wires penetrate the mag box outside the access hole cover or through the mag box sidewalls or firewall itself. Attachment of the heavy electrical cable and "T- handle" control to the starter is readily accessible thru the cutout. The only attachment to the cover is a bolt that supports a pulley for the pitch trim system. Even then the removal of the cover does not require the removal of the pulley bracket. The cover is removed and simply set aside with the bracket, pulley and cord attached.

Dick Barbour, Rogers, AR

FROM THE EDITOR

I asked several experienced people to share their opinions about flight-testing last year when I was working on the taxi test protocol I printed. Jack Harvey was one who responded with the following thoughtful and well-written piece. He aimed his remarks for the least experienced pilots.

FLIGHT TEST CONSIDERATIONS: Jack Harvey, FL

Do not assume that everything is going to be wonderful and the first flight will be a pleasurable experience. More than likely the opposite will be true. In spite of all the time you spent building the plane and all of the care you took constructing it, there will probably be a few things that need adjustment. Some of those could cause you considerable difficulty once you become airborne.

For that reason, I would recommend a runway at least 5,000 feet long and 100 feet wide for your initial test hop. If you have control or rigging problems, excessive oil or cylinder heat temperature (common occurrences on homebuilts), you may have to land immediately. Trying to handle an in-flight emergency and still squeeze an unfamiliar airplane into a short, narrow strip may be more than you care to cope with on the first flight.

Play it smart, have everything going for you that you can. Try to make the initial test flight early in the morning when winds are calm or light and the cool temperature will give better performance and smoother flying. An out of rig airplane on a hot, gusty, bumpy afternoon is going to make control more difficult and will tend to confuse your perception of any control problems.

You should definitely avoid making the first few flights late in the evening, for the simple reason that if you have to make an off airport emergency landing, rescue efforts will have to be conducted in the dark and it will be difficult to locate your plane. In that event, if you are injured, any delays that ensue before help reaches you will seem like an eternity and could even be life threatening. Above all, keep your enthusiasm under control and resist the temptation to try to "squeeze in" a quick first flight just before dark. The first flight is no time to put yourself in the position of having to hurry as well as operate in decreasing visibility.

Plan to hold your first few flights to 30 minutes or less even if things seem to be going well. That unsaftied nut or untorqued bolt could be slowly loosening under your cowling, so keep it short, land, uncool your little gem and check EVERYTHING carefully before your next flight.

Don't forget - if operating from a controlled airport, you are required to notify the control tower that you will be making a first time flight in a homebuilt.

BEFORE TAKEOFF:

Remember, this will be the first time your plane has experienced the stress, strain and pressure of actual flight, so be mentally prepared to encounter inconveniences like the aircraft being out of trim, canopy or speed brake popping open, sticking throttles and high cylinder head or oil temperatures.

Try to plan for those possibilities ahead of time, and think about what your actions should be in the event those things actually occur. Expect some control difficulties like a nose heavy feeling or a rolling tendency in either direction and try not to over-control.

If you have been flying planes like Cubs, Cessna 152's or Champs, be prepared for more acceleration than you are used to.

If circumstances force you to make the first flight at mid-day during the summer, you can also expect to experience considerable discomfort from high cockpit temperatures and the irritation of sweat running into your eyes with subsequent burning and blurring of vision. There is an awesome greenhouse effect inside that pretty, streamlined canopy.

My first flights were flown in winter in Florida and my cockpit ventilation problems did not become apparent until months later when I finally made a summer flight in early afternoon. I had the recommended air scoops on each side of the cockpit and they had seemed adequate earlier in the year. However, on that particular afternoon, immediately after takeoff I was forced to make one quick, almost frantic circuit of the pattern while cockpit temperatures climbed rapidly above 120 degrees. After that experience I added an air scoop to each side of the canopy skirt just below the Plexiglas and the problem was reduced to an acceptable level.

AFTER TAKEOFF:

If you are having control problems like a rolling tendency, keeping the aircraft near climb or slow cruise speed should help relieve some of the pressure.

Try to make control movements as smoothly as possible. Plan to stay in the traffic pattern and in close to the field in case something goes wrong. As soon as you have everything under control, check your gauges as methodically and as often as you can, paying particular attention to the oil pressure and temperature, the cylinder head temp, and the RPM as well as airspeed - but don't forget to look outside! Remember, you are flying a very small plane that has an unusually thin head-on profile, which is extremely small and difficult to see. Not only will you have to be concerned about intercepting other planes on a collision course, but with this aircraft at normal cruise speed you will also quickly overtake many of the older small planes which will be cruising 50 MPH slower than you.

CRUISE:

A nose heavy feeling that can't be trimmed out with elevator trim can be improved by cautiously increasing the amount of aileron reflex. Plan to make all initial maneuvers of any type small and gradual. Once you are sure everything is going well and you are beginning to get the feel of the plane, then you can increase the envelope of action.

If you decide to check pitch-buck speed on the first flight, climb to at least 2000 feet before doing so. Don't forget to check your cylinder head and oil temp during the climb. This is the time you are most likely to have problems with either one. When you perform the pitch-buck check, make sure you are out of the traffic pattern, but in case you have a sudden unexpected problem, you should stay as close to the airport as common sense allows.

One note of caution here - stalling an aircraft that has a CG out of limits or is experiencing even moderate control problems can be a risky business. If you are experiencing either or both of those problems this is the time you will most appreciate having a long, wide runway in front of you. If that is the case, you may want to cancel your plans to check pitch-buck speed and carry enough speed on final to insure safe flight and still have enough runway to make a safe rollout.

In any event, before checking pitch-buck speed, make sure the aileron reflexor is at its lowest setting. Too much reflexor coupled with an aft CG could possibly give you a deep stall - one where the rear wing stalls first. If that happens you could fall tail first, and so far I have not heard of a successful recovery technique for that condition. When you try the speed brake (belly board), make sure you have your airspeed below the recommended maximum, and be certain you have a good grip on the handle before you unlatch it.

DESCENT:

On descent you will need to pay attention to your RPM. Even though this is a fixed gear aircraft, it is a very clean airplane and if the power is left at cruise when you begin a descent, the airspeed and RPM will build rapidly. Naturally, engine operation above RPM redline should be avoided.

AFTER LANDING:

If you have enough runway remaining, plan to let the plane slow down to 30 MPH or less before using brakes, and even then, use them gradually and cautiously.

Dear Jim,

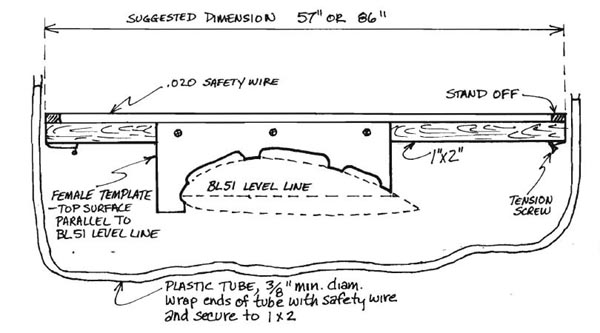

On the subject of setting the incidence of the wing and canard, for a few bucks a device can be constructed that will give accuracy to the tenths, maybe hundredths, of a degree.

First, a female template of the top of the airfoil is made using the original hot wire templates. I used BL51 templates on my Quickie. CAREFULLY transpose the level line to the top of the new template. Next, attached a relatively straight 1"x2" piece of lumber to the template. Center the template on the 1x2, trying to align the level line with the length of the wood. Make side supports on the template so that it will set on the airfoil without falling over.

One each end of the 1x2, add a piece of wood to act as a stand-off - 3/8" to 1/2" thickness will be fine. Secure .020 safety wire at one end, bringing the wire over the stand-off, routing it to the other end over the opposite stand-off to the underside of the 1x2. You should make some provision for the tension adjustment on this end. I used a long sheetrock screw, screwed in at an angle.

Now you have to calibrate it. With the wire very tight, carefully measure from the level line on the new template to the safety wire. Make the wire parallel using shims at the stand-offs. The more accurate you are now, the more accurate the finished product will be. Place the level finder on the airfoil. Take a length of at least 3/8" diameter clear plastic tube and attach it to each end with a nice droop under the wing. The ends should extend 2" above the wire level. Fill the tube with colored water and a couple of drops of dish soap (this is used to decrease the surface tension of the water so that you can more accurately "read" the meniscus or end of the water column. - ED.) When both ends of the wire and the water level agree, you have a level wing. A one-inch rise in a horizontal distance of about 57 inches is one degree. My levelers were made 86 inches long so one degree difference would indicate 1.5 inches between the water level and wire level on one end while the opposite end levels would be the same. A machinist scale measures as little as 1/32" on my setup. That comes out to .02 degree!

Dennis Clark, Newnan, GA

Dear Jim,

October 20 at 1300 hrs. I became airborne in my Quickie. I was really elated at the performance. I was off the ground in less than 500 ft. and started climbing effortlessly to 100 ft. I then throttled back, established a 65 mph approach and greased it in for the first time. It handled like a playful kitten, eager, responsive, sensitive and all airplane. The sensation of flying with the nose and prop beneath you in horizontal flight made me think I was in a dive but I quickly adjusted to the new view.

I made a total of 5 TO's and landings, all averaging good or better. All this was done on 5,800' ft. of runway in about 30'. Being carried away with this new achievement, I failed to keep track of my 1.5 hrs. of allowable engine running time and my engine quit as I exited the runway after the last landing. Back at the hangar, I propped the tail up 15" and drained out the last fuel - about 3 oz. So one can get complete gas drainage before the engine will quit! My original fuel float became gas logged and is inoperative.

Enzo Fraschini and his partner who are building a Quickie in Italy came by for a visit in October. It was real camaraderie. Their rules and regulations are much more stringent for homebuilt aircraft.

Jim, thanks for all your help and encouragement and also to all the other guys, especially Terry and Charlie, for their assistance too.

Ted Kibiuk, Holland Patent, NY

ED. NOTE: Human errors are often extremely insidious; they sneak up on you at the most thrilling times. Ted has been almost excessively careful in testing his airplane yet at the very last moment almost, when he was delighted with success, he could have lost it. Suppose he had decided that testing felt so good that he'd just make a quick run around the patch. His number would've come up. This exact thing happened to a beautiful DFW area Vari-EZ which ran out of gas (after a long series of taxi testing) just after crossing the airport boundary on climb out.

Dear Jim,

I bought my Quickie in 1980 and completed the fuselage by '83. Owing to a house building/children producing program, I didn't do much more. Low power and unreliability along with my low pilot time made me doubtful also. Now with the more powerful 2-cycle installations and the vortex generators my faith is renewed and I'm building again.

I live in a mountainous region; has anyone tried a belly board on the Q-1? (Not to my knowledge - ED.)

Barry Charlton, Otago, New Zealand

Dear Jim,

...it starts to look like something...visitors already stay longer inside my workshop and begin lucrative conversations. Lately, Jack Kofler and me were chatting and designing an emergency release system for forward hinged canopies especially when Quickies rest upside-down after landing. The system is usable for normal open/close operation from in/outside with integrated emergency function. The mock-up looks simple. I just need to transfer the installation to the canopy. I will send more information when successful results are available.

On the administrative side of project #137/E...At the Swiss RSA (EAA counterpart in Europe) meeting, a seldom chance was offered. I was able to talk to Gerhard Gugler, builder of Quickie HB-YCC (22 hp Onan) and frequent flyer. Year of construction: 1984. Quickie 1 is a known homebuilt aircraft for the Swiss FAA (BAZL). Gerhard's Q-1 was successfully load tested at an ambient temperature of 54 degrees centigrade. Well, well...now asking my standard question: From which source he obtained OFFICIAL wing load calculations for his Q-1? His answer was clear, good old QAC supplied all necessary figures. Jim, I'd like to puzzle together Quickie Q-2 history, as it seems QAC must have played his part in Q-2 construction. Did they ever release official Q-2 wing load calculations? If they have done it, who is sitting on the SECRET today after QAC pulled out? Months ago I wrote to Sheehan Engineering...answer still pending.

Rudi Brandenberger, EUROPE

ED. NOTE: It would make the lives of European builders much less difficult if the official wing loading figures were available to them. So far as I know, they were guarded proprietary information that was never made public. If anybody has them, I'll spread the word thru Q-TALK.

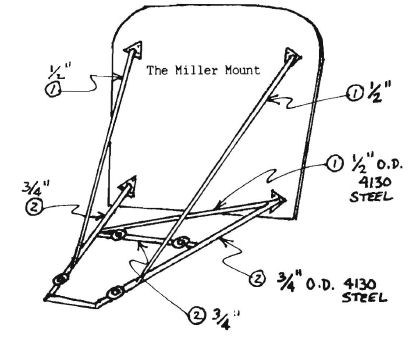

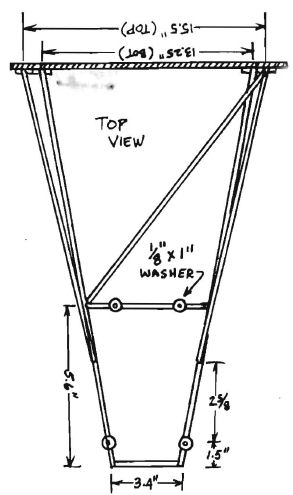

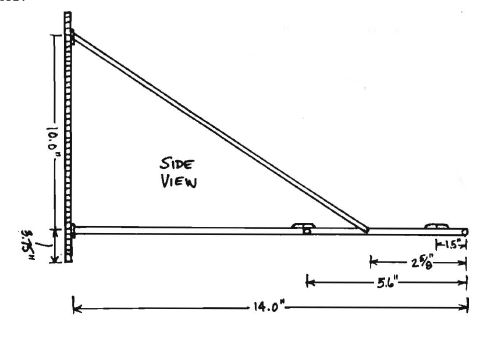

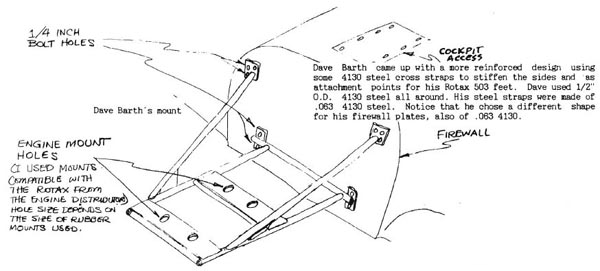

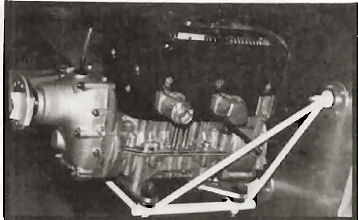

In Q-TALK #23 we took a look at the kind of things that QBAers have done to strength the Quickie firewall to take on the extra power of the Rotax 447 and 503 engines. The range was from nothing at all to the carefully planned work of Hawks/McCaman. This time, let's take a look at what kind of mounts have been fabricated to hang the engine on the firewall, and again, these range from the simple to the "bulletproof" version of Jinx and Brock.

The first drawings here depict the mount used to mate a Rotax 447 to the Quickie. This is the no fuss, no muss design that Miller showed up with at Oshkosh a few years ago. So far as I know it has worked just fine. Notice the attention to lightness. The 4 engine attach points are made of 3/8" I.D. 4130 or bushing stock welded into the tubing and capped off with a 1/8"x1" diameter washer. Note also that the firewall mounting plates are triangular shapes of .100" 4130 and that they are partially attached via the 2 outside bolt holes already drilled for the Onan mount.

All these dimensions are approximate. Miller used the engine itself and his firewall to get the exact numbers.

Next time we'll look at the Barth mount in more detail and examine the Hawks/McCaman configuration.

A nice, simple mount. Note the shock mounting.

Dear Jim,

Please find enclosed $20 for the renewal of my subscription to "Q-TALK". Thank you again for your efforts in producing our lifeline to information on the Quickie scene.

As usual, I am making much slower progress on the conversion of my Quickie to Rotax 447 power than I had expected, but it is still going ahead. I have had my engine mount checked by a stress analyst at British Aerospace and the engine is now sitting on it on a stand in the house. Switching to dual carburetors slowed things up because it meant modifying the mount. The exhaust system has been cut in many places and welded back together in the contorted shape necessary to fit inside the cowling in front of the firewall. I have shortened it by no more than about 1 cm. and I hope this will not have a significant effect. I am using a standard Ed Miller pattern cowling and am just finishing changing its shape to remove the muffler bulge and streamline the front. The next step is cleaning it all up, painting it and putting it on the airframe and fitting the plumbing (including an electric fuel pump) and the controls.

The paint finish on the aircraft was acrylic on top of cellulose UV barrier and Feather Fill. After 4 years this has blistered so badly through osmosis and subsequent freezing that it will be necessary to repaint the whole airframe. Has anyone else had this problem? Can anyone recommend a finish that will not suffer this way?

Yours,

Martin Burns

Dear Jim,

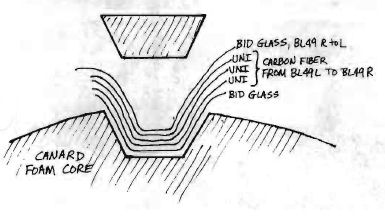

Here is some information on the Q-1 that we are building in Argentina. On the canard we have made a spanwise stiffener from left BL88 to right BL88 with carbon fiber as in this drawing:

We are building the canard strong because in our country, most of the runways we are able to use are of grass.

When we installed the wheelpant, we put a straightedge parallel to the LG4 inboard insert and another straightedge on BL00. We made two marks on the wheelpant straightedge and then transferred those marks to the BL00 straightedge. When the distance between the two straightedge marks is the same, we will have the wheelpant parallel to BL00. We did the same thing with the other wheelpant, always taking into account the measurements taken previously. As a consequence, we will have "0" toe-in and "0" toe-out, and if we verify with a plumb bob, with the inboard insert in vertical position, we will get "0" camber.

Carlos Escobar, Argentina

Dear Jim

My bird is in storage for a while until I complete a ProTech PT-2. Soon as it gets in the air ... back to the Q-2 I go. It got so each time I got near the Saf-T-Poxy, my hands would nearly fall off. It's been like that for more than 8 years. I guess I'm too dumb to give up on it. Anyway, you gave us 'til 2000 to finish 'em!

Bob Bird, Friendswood, TX

Dear Jim

Quickie N5425D has about 25 hours since its first flight. I had one engine mount bolt break at about 25 hours but no other problem since then. I enjoy flying the Quickie very much. Q-TALK has helped to make this possible, and also safer, because of all the information shared by other builders. Thank you.

Arden Krueger, Wausau, WI

ED. NOTE: A broken engine mount bolt is not an uncommon problem. Quickie pilots should include this in all preflight checks.

Dear Jim,

I cured the wing by building a plastic tent around it and using hair dryers to get the temperature up to about 160 degrees. How have others gotten along using this method?

I'm now building the canard in my second story apartment and am planning to take it out via my patio door after curing and mounting the wheelpants. But as everyone knows how good plans go, we'll see.

Robert Bone

Dear Jim:

As you know, I'm a retired Navy pilot and a recent law school graduate. I've heard stories of homebuilders destroying their aircraft or donating them for display purposes rather than risk a potential lawsuit. I hope my comments alleviate some of the misunderstandings and apprehension that exists on this subject.

There is an excellent discussion of potential homebuilder liability in the May 1990 issue of Sport Aviation (page 62). The article points out there is not very much law on the subject; that is, few or no cases on record. I searched for cases using a computerized legal database, which contains state and federal cases that rise to the appellate level; cases whose results are appealed. I was not able to find a single case involving someone being sued after building and selling a homebuilt item; car, aircraft, seesaw, etc. I was only able to find 2 cases that even referred to homebuilt aircraft. One case involved a Vari-Eze being used to smuggle drugs. The second case was Mullan v. QAC, the case that sunk Quickie Aircraft. If you want to read the QAC opinion, your local courthouse library has the case 797 F.2d 845. The librarian will point you in the right direction.

Here's a brief glance at the legal theories a homebuilder may face in a lawsuit. First, breach of contract. If you sell a product, stating it will perform in a certain way, you can be held liable if it doesn't perform as you've specified. However, you can choose to make no claims when you sell a product; sell it "as is, with all faults" and probably not be held liable for breach of contract because you made no performance promises to the buyer. I regret I must use the word probably, but in the words of one of my professors, "Anything that goes before a jury is a crapshoot."

Next is the tort recovery theory. A tort is simply a civil wrong. One type of civil wrong is negligence; failure to exercise reasonable care. If you operate your automobile or aircraft in a negligent manner, you can be held liable for any damages that are the direct result of your negligence. If you build an aircraft in a negligent manner and damage results, you can be held liable for the damage if your negligence can be proven.

Finally, we have product strict liability. This California product of the 60's is also a tort, but with a different twist. Historically, someone injured as the result of a defective product had to prove the product was manufactured in a negligent manner, normally very hard to do. This new tort theory was based on the premise that the manufacturer should be liable for physical damage caused by a defective product because he's in a better position than the product user to absorb injury costs. The manufacturer can then spread these costs across the entire spectrum of users. Note that the manufacturer is responsible even though he may have exercised the highest degree of care in manufacturing the product. The injured party need only prove the product was defective, and the defective product caused the injury. This tort recovery can only be used against someone in the business of manufacturing a product, or depending on the state you happen to live in, someone in the business of selling the product. This recovery theory is now the law in most, if not all, states. However, it has NOT extended (at least not yet) beyond commercial manufacturers.

The most probable basis for a suit against a homebuilder is negligence. Most of you remember Bob McFarland and the details of his accident. What you may not know is that Bob's estate was sued by Tim Firestone's (Bob's co-pilot) estate on the theory that Bob's negligence caused Tim's death. The negligence issue centered around the wing main folding in flight as a result of Bob's wing repair following an earlier accident. The Firestone estate later dropped the suit against Bob's estate because the technical expert could not provide sufficient evidence to support the negligence allegation against Bob.

The question whether to sell a homebuilt and risk a potential lawsuit is a very personal one; there are no right or wrong answers. I intend to sell my Q-2 when the time comes. To minimize the lawsuit potential, I will take steps to reduce the possibility of a contract or negligence claim against me. I will maintain a comprehensive aircraft builder's and maintenance log. I will be scrupulously honest with a potential buyer. I will not brag about the aircraft's performance. If anything, I will downplay it. I will sell the aircraft as is, with all faults. I will emphasize the fact that the aircraft is EXPERIMENTAL, and does not comply with the many FAA directives that apply to a commercially built aircraft. All this will be in a written bill of sale. If I weren't a lawyer, I'd probably consult one to help with the sales contract drafting.

In summary, none of us can be entirely free from a possible lawsuit in this litigious age. This applies not just to our homebuilt aircraft, but also to our entire spectrum of daily activities. Insurance helps, but all policies have limits, and it's possible for damage awards to exceed those limits. However, we can help ourselves by making it as difficult as possible for someone to be able to prove an allegation of negligence against us.

Ray Isherwood, Tallahassee, FL

My tip for this letter is for swinging your compass. Buy a Silva explorer compass ($6.95) and masking tape it to the canard tip or horizontal tail surface. Level with wood blocks as needed. The Silva compasses have adjustable dials and can be read to one degree. Align the airplane with some distant object if possible and fold an index card at right angles for a sight to aid in aligning the Silva compass.

Now start at 090 by Silva and use E/W adjuster to get 090 on the airplane compass. Next rotate the plane to 180 by Silva and use N/S adjusters to get 180 on the airplane compass. Thirdly, rotate the plane to 270 by Silva and read the plane compass. The difference between the Silva (270) and the plane compass is the error. Use the E/W adjusters to reduce the error by 1/2. Now rotate to 000 by Silva and read the error again. Use the N/S adjuster to reduce that error by 1/2 and you have now corrected your compass.

Obviously, you should have no metal objects (screwdrivers, knives, etc) in your pockets while adjusting your compass.

With the compass now adjusted you can rotate to the 30 degree intervals by Silva and fill out the compass card.

There is a more sophisticated way of doing all of this, which is slightly more accurate, but it involves a lot more math. The compass adjustment is the same. There is a government publication called Magnetic Compass Adjustment which gives a lot of information on compass errors.

As an alternative a square wooden block carefully placed horizontally with a vertical rod may be used as a sun shadow compass obtain exactly 090-degree rotations. Work quickly, the sun moves 15 degrees per hour.

I helped John Groff swing his compass. I wrapped his electrical turn and bank with Mu-Metal (a tin can would also work) spaced by foam to reduce the field from the DC motor. The worst compass error is 4 degrees. This appears to be caused mostly by the engine crankshaft. This error could be reduced further but it doesn't seem worth the work.

Some computer calculations indicate that the lowest drag cruise for the canard LS(1)-0417 airfoil is with -5 degrees of flaps (up). This reduces the canard drag by about 15%. You should experiment with trim in flight with your airplane to find the optimum. The main wing Eppler 1212R does not seem to change drag much with reflexor trim according to my computer using Airfoil II.

Steve Whiteside, Ringwood, NJ

Hi Jim,

Gary LeGare's prototype Q-2 "Fatso" was involved in a pilot error type accident in Edmonton in the fall of '89. The current owner plans to rebuild so it should be back in the air sometime in the future.

Arnold Forest, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada

ED. NOTE: Since this airplane is THE very first Q-2, I think it is historically significant. Arnold, any further info on the accident, the specific damage, change of ownership, repair and re-flight may be of great interest when some historian paws through this stuff to gather the history of these designs. Please keep us informed.

Dear Jim,

I now have 275 hours on Q-2 N275CH and still find it as much fun as ever. I have given about 40 rides with great responses from all passengers. The specs on 275CH are:

Empty weight, 632 lbs. Warnke 60x68 prop on the front of an 0-200. True airspeed at 2850 rpm is 190 MPH burning 5-5.5 gph auto fuel. True airspeed at 2450 rpm is 170 mph burning 4.5 gph.

Charlie Harris, Littleton, CO

Dear Jim

My new nose gear leg made of heat treated 1 1/8" OD x 1/8" wall 4130 tubing is working out well. Much stronger and stiffer. Thanks to John Groff for the trail blazing design. My Tri-Q-200 is so reliable and predictable that it's almost spooky. Never misses a beat.

For you guys still building, hang in there. There's nothing quite like climbing out on a cold winter morning at 110 mph and watching the trees get small at 1600 fpm. Or taking off after a Cessna 172 has departed only to pass him up moments later as you tell yourself once again, "No, a Cessna CANNOT fly backwards!" What a rush!

Mitch Strong, NY

In case you're wondering where the composite education section that was ballyhooed last issue went to, he must've fell asleep after the last letter. Or...maybe he forgot to change his CALENDAR when time went "fall backward" last month - ED.

You can order a PDF or printed copy of Q-talk #24 by using the Q-talk Back Issue Order Page.